If you’ve spent any time in writing circles, you’ll have heard about “pantsers” and “plotters” - people who write books by winging it (flying by the seat of their pants), and those who tightly plot their stories top to bottom.

I used to be a panster. My debut, Hell Followed With Us, was pantsed…and that was how I discovered I, in fact, should not be a pantser. I’ll keep it short and say that editing it sucked. When it was time for my second novel, The Spirit Bares Its Teeth, I tried to course correct - but I didn’t go far enough, leading to the most difficult months of revision I’ve ever experienced. We’re lucky TSBIT is on shelves at all.

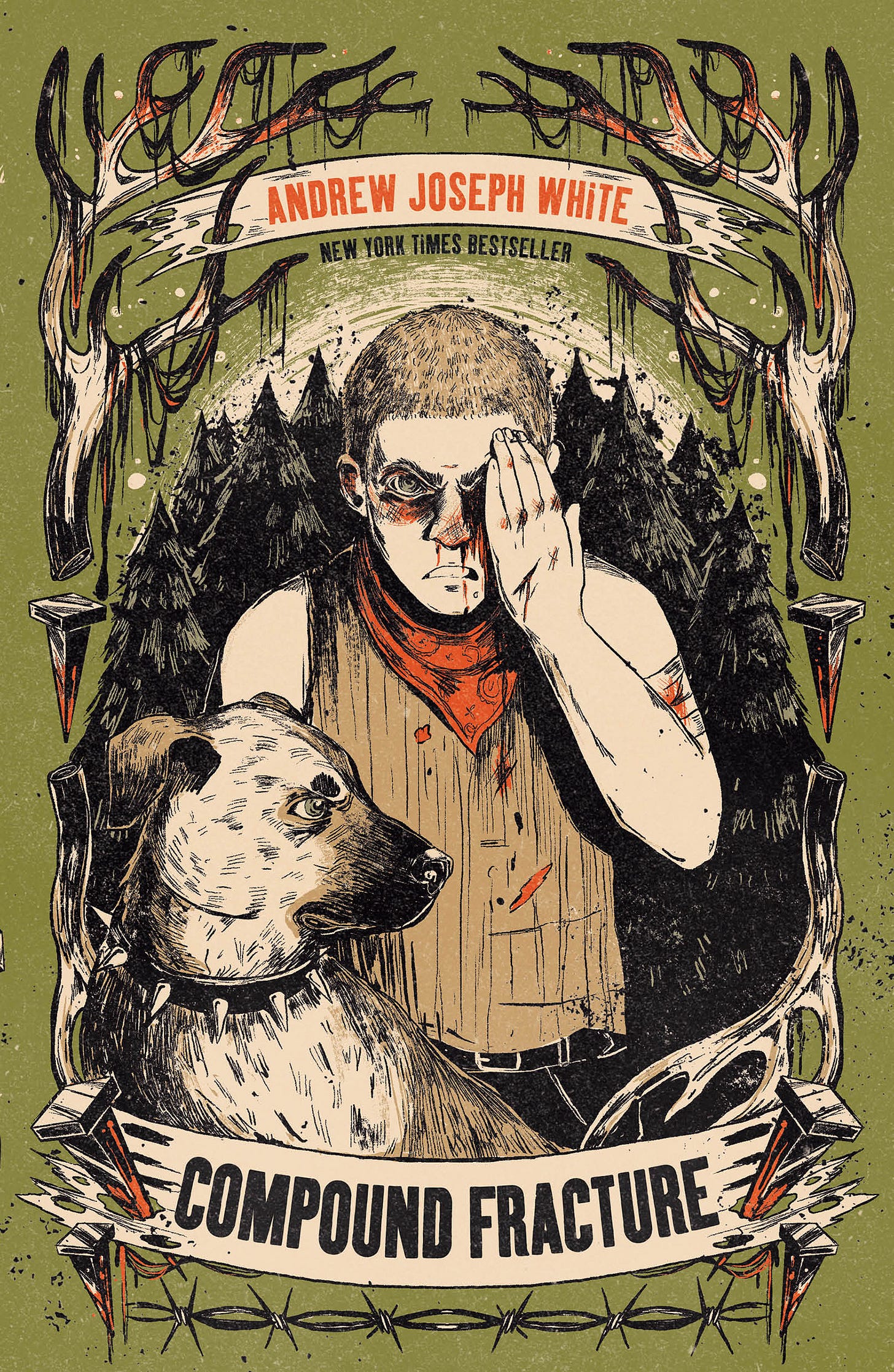

I’ve learned my lesson; these days, I create a specific set of planning documents before I even dare to start drafting. And, you know what. I hit a milestone with this newsletter. (Already!) So let’s go over it, using the materials I created for my New York Times and Indie bestselling YA novel, Compound Fracture.

When plotting a book, I create the following:

Logline pitch

Mock-up cover copy

Thesis statement (optional)

Chapter-by-chapter outline

(A quick side note: Compound Fracture underwent a lot of tightening after these materials were created, so they may not fully or accurately reflect the final book.)

Logline Pitch

This is relatively straightforward - how do I sum up a book in one sentence?

Books are big and complex, 300+ pages with a lot of moving parts. It’s easy to get lost in the details. So before I delve any deeper, I have to boil the concept down to its most basic throughline. What is the driving force here? Am I able to concisely explain what the book is about?

Compound Fracture’s logline looked like this:

An autistic trans boy from West Virginia survives attempted murder with the help of an ancestor - a miner executed in the coal wars - and tracks down his attackers to end the blood feud between his family and the local sheriff’s.

If you gave me a day or two, I could improve this. The wording isn’t quite right, and it leaves out a lot of the political context driving the plot. But it’s an easy elevator pitch for a marketable story, and that’s what I needed at the time.

Mock-Up Cover Copy

I do a lot of things to make a book feel “real” while I’m working on it. My drafting document has bizarre margins meant to mimic book pages. Sometimes I build fake deal announcements just for the thrill. And I also draft a mock-up of the cover copy - that is, the summary you find on the inside flap or back cover of a book on the shelf.

If you’re querying or pitching a book, you’ll have to write something similar to this anyway, but I do it early in the process. It expands on the logline, gives the story more depth, and helps me flesh out the conflict.

Compound Fracture’s mock-up cover copy looked like this:

In 1917, Saint Abernathy—socialist, young father, and figurehead of a labor strike in the mountains of West Virginia—was publicly executed by law enforcement. In 2017, Miles Abernathy—his great-great-grandson—wakes up in the hospital, the latest casualty of a blood feud that began with the railroad spike hammered into Saint’s mouth.

Miles, a seventeen-year-old trans boy, knows he’ll never see justice. The sheriff’s son and his friends leave destruction in their wake, dead bodies and trauma too deep to dig out. If Miles speaks up, says they’re the ones that did this to him? He’ll be lucky if his parents are alive enough to flee the state.

But then Miles kills one of the boys who hurt him, and Saint Abernathy is back, a century’s worth of fury and revenge, saying that Miles might be the one to end this feud once and for all. To free his family from a hundred years of cruelty, all Miles has to do is finish the job—and murder the rest of them.

Is it fully accurate to the story as it now stands? I don’t think so. You can see the current cover copy on my website. And there are much older mock-ups that don’t mention Saint at all, give side characters more weight, etc. But again, it gives me a place to start, and that’s what matters.

Thesis Statement

Every piece of art is political - at the very least, reflecting the political conditions under which it was made. Even books that contend to be normal fail to understand that what is “normal” is political in and of itself. Every book says something whether it means to or not.

So the least I can do is be aware of what I want to say. That’s where the thesis statement comes in.

This doesn’t have to be fancy. It can range from a bubble map tracking all the branches of a metaphor (like I made for The Spirit Bares Its Teeth) or a sentence at the top of a planning document. Hell, Compound Fracture didn’t have one at all. I’d carried the story with me for so long that I didn’t need it. But here are some other examples:

I jotted this in a notebook during therapy while discussing my upcoming YA You’re No Better:

Kids with demonized/“ugly” symptoms and trauma responses deserve to be something other than the antagonist

For my adult novel, You Weren’t Meant to be Human, I put this down on a scrap of paper while working on a revise & resubmit for Saga Press (yes, authors get R&Rs while on submission too!):

post-Roe horror/abortion is healthcare/pregnancy is body horror/pregnancy is violence/we’re angry and scared and i’m going to shove it in your face

Figure out what your book is saying. Verbalize it. And when you inevitably get questions from readers about the theme, you’ll already have an answer. (This is also when I inspect the implications of allegories and confirm my ability to do the story justice. I take a lot of care here. I encourage you to do the same.)

Chapter-By-Chapter Outline

Now that I have this supporting information - the logline, the pitch, the thesis statement - and understand what book I’m trying to write, it’s time to figure out how to write it… with the help of an outline. My outlines usually clock in at ten pages single-spaced. They are painfully in-depth, extremely hand-holdy, and leave as little as possible to the imagination.

They have to be. If they aren’t, I will default to BS plot devices, contrived coincidences, and so many deus ex machinas. I will struggle with scene progression and make bad decisions that are hard to untangle. I will, in short, look like I’m awful at my job. It’s best for everyone involved that we get as much detail correct at this stage before moving on.

Did I fully manage that with Compound Fracture? Not entirely. I was still learning about how I need to plot my work. But I made some improvement, so I’ll take it. Below is a screenshot of the plotting document I used back in 2022; the black bars cover up information no longer relevant to the story.

Is this in-depth? By my current standards, absolutely not. The above example has about two chapter’s worth of information - in the final draft, 5000 words or over twenty pages. Below is an example from my most recent planning document. (A sneak peek at an upcoming YA!) The information here covers one chapter - about 2700 words or eleven pages. It reads more like a script treatment for a movie than an outline, but that’s what I need.

Also, notice how clean this is? That’s because I also use my outlines as synopses - to prove to an editor that I can tell a good story. Two birds with one stone.

But wait. How the hell do you actually do the plotting? That part sucks.

God, you’re so right. It so does.

That’s why I try to make it at least a little fun. I keep lists of kickass scenes I want to include. I think about which characters would have the worst time in the same room, and what terrible things I could do to them. I listen to music too loud and daydream.

In a more structured way, I build a chapter skeleton to stitch all that daydreaming onto. Most of my books hit the 80,000 to 90,000-word mark, and my chapters run in the 2,000 to 3,000-word range. If you do the math, that’s 30 to 40 chapters, so I make a document with around 35 bullet points and jam events onto the line as I go.

(As an additional resource, both my wife and I have been using this article for literal years to help with plot structuring: How to Outline Your Novel with the Save the Cat! Beat Sheet.)

Then, once I flesh out the bullet points as much as possible, I give it to someone else and ask for feedback because plotting is hard and I don’t like it.

Wrap-Up

By the time I sit down to start working on a manuscript, I already have several thousand words of information supporting the blank page. Without that information, I panic and make bad craft decisions. With that information, I can focus on telling a good story.

People talk about writing being discovery. I know some friends who, if they plot beforehand, no longer feel that spark of learning about the story, the characters, the world. They lose interest. If plotting a story destroys your love of it, don’t! But if you’re anything like me, discovery of the story lies in the minutiae of character interaction, the specifics of dialog, exactly how I pull off what I promise in the outline. Plotting helps me get there.

Thank you all for 500 subscribers, and I look forward to sharing my next book with y’all.

Amazing! Definitely will take some of this advice into my own writing!

this was so straightforward and succinct, but thank you especially for sharing your behind-the-scenes. it's 10000% more helpful with some real examples.